When we think about language learning, many of us immediately focus on vocabulary lists and grammar rules. In theory, with the right set of memorized words and structures, we should be able to apply the knowledge and communicate properly. This is the logic that drives many high school language classes. However, we’re overlooking something very important. Language chunks, the combinations of words and phrases used by native speakers.

Unfortunately, many of us have studied a language for years in high school and have little to show for it. There has to be a more effective method. Today, I want to talk about language chunks—what it is, why it matters, and how it’s helped me in my own language journey.

What Are Language Chunks?

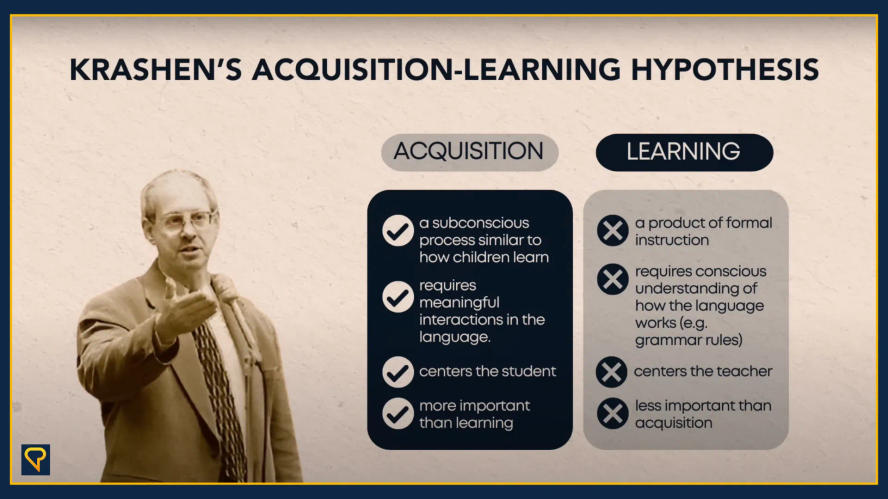

Traditionally, language learning has focused on individual words and grammar formulas. But research and experience tell us that this is not the right approach.

Much of any language—up to 60%—consists of formulaic expressions, or “chunks.” These are groups of words that naturally go together. In English, examples of “chunks” include:

- “By the way”

- “On the other hand”

- “Would you mind if…”

But chunking goes beyond just common expressions. Almost every word in a language is typically used alongside other words in specific ways. This is why word choice is often the real challenge for language learners who want to speak more naturally—not grammar.

If you want to sound natural in your target language, learning how native speakers use words together is key. Chunks are how we build fluency.

How to Learn Languages in Chunks

Some people suggest learning chunks the way you would learn phrases from a phrasebook—memorize, repeat, use. Personally, I can’t remember prefabricated phrases out of context. I find more success in acquiring chunks when I encounter them in meaningful situations.

Immersing ourselves in our target language through conversation, listening, and reading exposes us to the language as it’s naturally used.

Research from Cambridge shows that students who spent time in France speaking and listening to French picked up natural-sounding chunks—not because they memorized them, but because they heard them often in context.

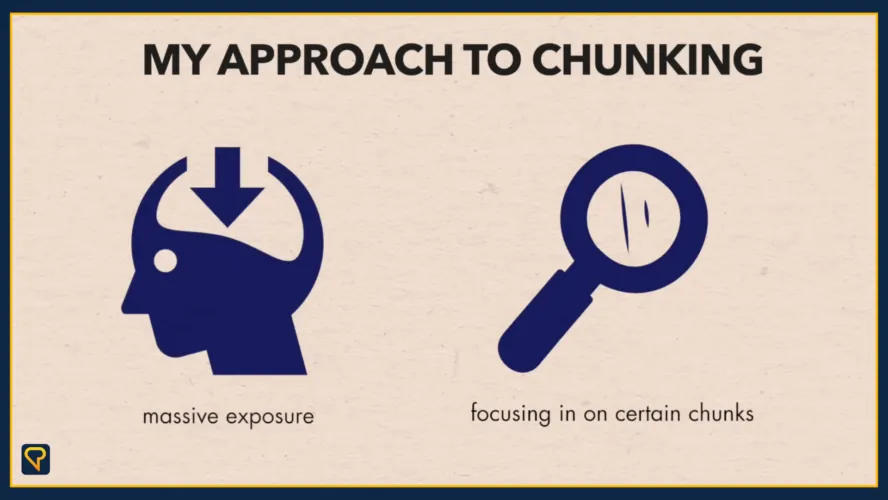

That’s how we acquire language: through massive, meaningful exposure. Not drills. Not flashcards. Real, compelling content. In other words, we don’t need to curate lists of chunks to learn a language. We just need to consume lots of compelling content, and let the brain do what it does best—recognize patterns naturally.

My Experience with Turkish

Take my Turkish learning journey, for example. I’ve been learning for about five and a half months. Producing correct verb forms is still a challenge. But I know from experience that it gets easier over time.

My strategy? Massive input.

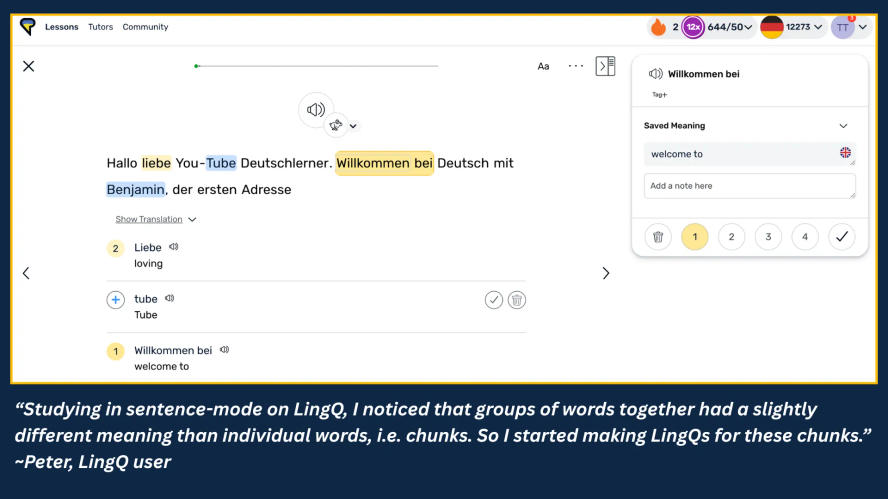

I listen to Turkish audiobooks in my car via Storytel. I don’t understand everything, but I catch certain chunks. Later, I read the same books on LingQ, highlight useful phrases, and review them in sentence mode.

That’s how I slowly start to use these chunks myself. I don’t memorize them—I acquire them.

This is a gradual process. It takes time to internalize chunks and reduce mistakes. That’s normal. Even now, I revisit beginner content—like the mini stories on LingQ—to pick up on new patterns and reinforce familiar ones. It’s a cycle: input, exposure, recognition, production.

Final Thoughts

Learning languages in chunks is more effective—and more enjoyable—than memorizing isolated words or grammar rules. Trust the power of comprehensible input, give yourself time, and let the chunks come to you.

comments on “How to Become Fluent in a Language: Chunking”