TL;DR Summary

A polyglot is simply someone who uses several languages. This open definition allows for a lot of variance. Some polyglots speak well, some mainly read, and some shift between active and dormant languages over time. Ultimately, aspiring polyglots should prioritize enjoying languages, not meeting arbitrary standards.

Am I a polyglot? I suppose so. I’ve learned many languages, and each language brings me a great amount of joy. I’ve crossed paths with many other polyglots, and we all seem to have different definitions. Some prioritize speaking well while others are content to simply understand their languages. In this post, we’ll explore different takes on what it means to be a polyglot, as well as what really matters when learning a language.

The Varying Definitions of a Polyglot

Anna Karenina begins with the line…

“Все счастливые семьи похожи друг на друга, каждая несчастливая семья несчастлива по-своему”.

Roughly translated, all happy families resemble each other, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. When it comes to language learning, I invert this sentiment. Unhappiness among language learners looks the same. We’re never truly perfect in another language. There will always be room for improvement in certain areas. Happiness, on the other hand, varies on an individual level. Language learners draw satisfaction from their studies differently. Some simply enjoy the academic enrichment while others strive for new connections, certifications, etc.

The Standard Polyglot

According to the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary a polyglot is simply defined as someone who knows and is able to use several languages. Speaking is not directly mentioned, and this leaves us with a more open-ended answer regarding what it means to be a polyglot.

The Conversational Polyglot

Some define polyglots by their conversational ability. I received a comment on my YouTube channel, pointing out that the etymology of the word refers to “many tongues” in Greek. This does imply that a polyglot should be able to demonstrate their knowledge of a language through speaking.

The Silent Polyglot

I remember visiting a café in Vienna in 1965. A man in the café drew a large amount of attention, as people would write down questions for him in 13 different languages. There wasn’t a question put to him in writing that he couldn’t answer. Why writing? Well, this man was deaf and mute.

Is this man a polyglot? I believe he is. However, he does not speak his languages. He relies purely on the written language to communicate. He is, in a sense, a silent polyglot.

Languages in Flux: Polyglots may need some refreshing

Our grasp of a language isn’t always very consistent. Like any skill, languages need to be constantly maintained. Let’s use Romanian as an example. Below are my statistics from LingQ.

My statistics on LingQ shows that I know 20,000 words in Romanian. I have a lumber business and we have suppliers in Romania. Ten years ago, I worked very hard on Romanian before a business visit. I spent two months studying the language to communicate more effectively at the mills. I spent my first month simply listening and reading Romanian. In the second month, I added some online conversations to my routine.

My Romanian: Then & Now

I had a great time in Romania. If you travel in Romania and decide to rent a car, you can hire a driver for an additional five euros per day! My driver was a university student, and he not only served as my driver, but also my impromptu guide and Romanian teacher for hours per day.

The mayor of the town that I visited would grab me and kiss me on both cheeks every time he saw me simply because I spoke Romanian. In short, my Romanian language skills were very well received!

A year later, however, I was in Edmonton and I needed to pick up a rental car. There was a Romanian girl there, but I couldn’t say a word to her. You can lose a language pretty quickly if you don’t take it up to a certain level. The realization that I had lost my Romanian was very disappointing, but I know that the language is still there, waiting to be refreshed.

Kató Lomb: A Polyglot to Admire

Kató Lomb was a very famous polyglot from the twentieth century. Completely self-taught, this is how she’d reply to the question, “How many languages do you speak?”:

“I have only one mother tongue: Hungarian. I speak Russian, German, English and French well enough to interpret or translate between many of them and then I have to prepare a bit for Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Chinese and Polish.”

As a polyglot, you may have to refresh a language every now and then. I’m sure that any polyglot who speaks several languages probably has five “ready to go” and another five that require a bit more preparation.

Lomb’s Take on Language Learning

Kató Lomb was entirely self-taught and, of course, this was during a time without mp3 files and Internet. Lomb’s method of choice to learn a language entailed working with a novel in her target language and a dictionary. Lomb didn’t stress over rare or complicated expressions, trusting she’d come across what was really important again sooner or later.

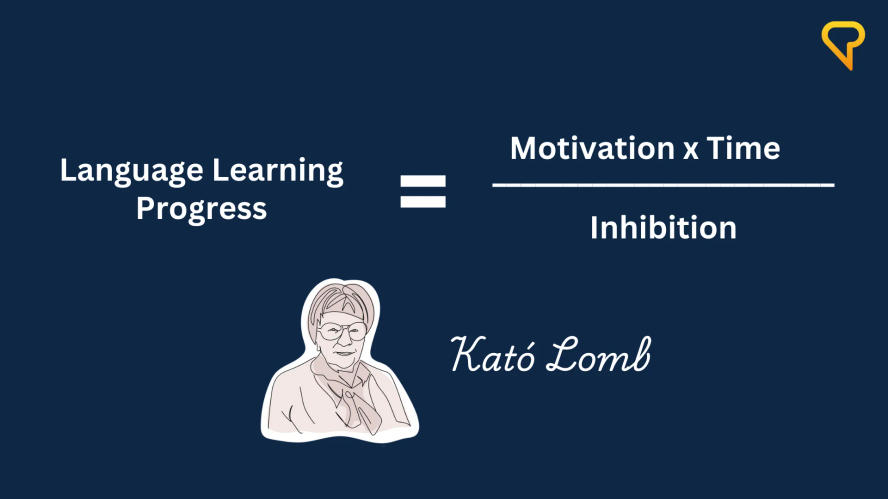

Kató Lomb brilliantly explained language learning with an equation. Language learning is motivation and time divided by inhibition.

In other words, you’ve got to maximize motivation and time with the language while minimizing your inhibition.

My Advice for Aspiring Polyglots

Language Learning as an Upside Down Hockey Stick

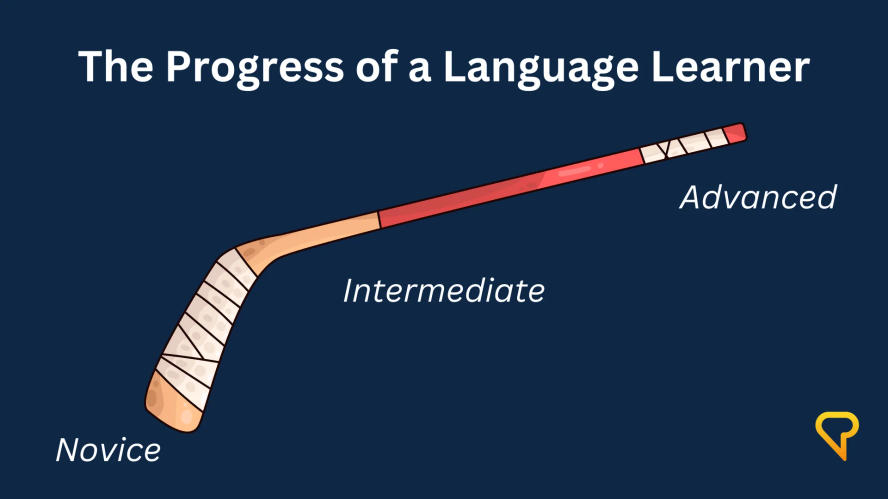

The progress of a language learner follows an inverted hockey stick pattern. In the beginning, progress feels steep—you’re learning new words quickly, and it’s exciting to go from knowing nothing to understanding and speaking. Even dull content feels rewarding because you’re discovering a new language and the progress is so tangible.

Then, after a few months, progress slows. You still struggle with many words, and comprehension feels just out of reach. People say knowing 1,000 words covers 70% of content; but in a book, it’s the rare words that keep blocking your understanding. It’s frustrating, but this phase is unavoidable.

The good news? Once you reach this point, you can access and enjoy more interesting material. Early on, you might use structured courses like Benny’s Teach Yourself series. As your comprehension grows, you can move on to real-world content—radio, movies, books—endless materials that keep pushing your skills forward.

Decide What Type of Polyglot You Want to Be

Not every language learner follows the same path. Some thrive on early speaking practice, while others prefer to immerse themselves in listening and reading before engaging in conversation. There’s no right or wrong way—only what works best for you.

If you love history, like myself, audiobooks can be a great way to learn. When I needed to refresh my German, I found an audiobook on German history, downloaded it, and started listening. I’ll often import what I’m reading or listening to into LingQ for the sake of review and convenience, as it’s available across multiple devices. I prefer the more immersive method, as I find that ample listening and reading enrich my vocabulary and translate into stronger writing and speaking skills.

Whether you prefer to speak early or focus on input first, remember that language learning is an individual journey. Even if you rarely speak, you’re still a polyglot—just a quieter one. The key is rich input, which leads to rich output. Find what excites you and build your learning around that.

Final Thoughts: What is a polyglot?

In short, there is more than one definition of a polyglot. We can be silent polyglots, talkative polyglots who don’t read, etc. We can be any kind of polyglot we want. The main thing is to engage with the languages, enjoy the process, and keep on discovering.

FAQs

1. What does “polyglot” actually mean?

A polyglot is someone who knows and uses multiple languages. Levels of fluency and mode of use, however, vary widely.

2. Do you have to speak a language well to be a polyglot?

No. Many polyglots engage with their languages primarily through reading and writing. Speaking is not the only criterion for knowing and using a language.

3. Can you forget a language if you don’t use it?

Yes. Language, like any skill, fades without exposure and consistent use. However, it can be revived. I doubt that a language is ever truly lost.

4. How do famous polyglots learn languages?

Approaches differ, but I particularly like Kató Lomb’s formula for language learning: Maximize motivation and time while minimizing inhibition.

5. What matters most for aspiring polyglots?

Every polyglot should enjoy their languages and the process of learning them. The method and purpose of learning a language, however, is an individual matter.

Want to learn language from content you love?

6 comments on “The Definition of a Polyglot”

Comments are closed.

Thanks Steve for another great post and for the useful resources. It looks like the debate of what is a polyglot will never end, but it’s not something I’m particularly worried about. It’s all part of the discussion of language learning.

My experience is also that certain languages need a warming up period to begin to flow more naturally. It’s almost like switching a chip on in our heads to turn on the other language.

Speaiing multiple languages and being flluent in multiple languages are two different things! Because I can say hello, how are you in 8 languages makes me a polygloot?

This should put to rest the debate as to what a polyglot is. Great article!

Lorsqu’on te demande un code postal ou une adresse sur internet, à moins que ce soit pour une commande il ne faut pas trop y attacher d’importance. Il suffit de regarder sur internet le format des codes postaux polonais et de mettre n’importe quoi, l’immense majorité du temps ça suffit pour accéder à tout ce que tu veux.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_des_codes_postaux_en_Pologne

Thank you so much, so much for share these ideias and thoughts with ours.

Brazil

Vitória – ES

1 year self taughted english.

Great ideas, thank you for sharing my regards, sir

ahlam from Algeria