TL;DR Summary

German took me a while to get used to. In the beginning, I just listened a lot and tried to get a feel for it. I didn’t bother much with grammar tables or endings — they didn’t stick anyway. After enough reading and listening, I developed a sense of intuition with German. I still make plenty of mistakes, but that doesn’t matter. The important thing is to keep enjoying the language and letting it grow on you.

***

I’ve always had a personal connection with German. My parents were born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in a community that later became part of Czechoslovakia. They spoke both Czech and German. Growing up in Canada, my brother and I resisted the language. In fact, we resisted everything to do with Europe.

As an adult, however, my interest in German grew. I wanted to travel to Europe and found work on a German ship. My initial attempts to communicate were horrendous, but my interest never waned. Later, I hitchhiked through Germany, worked briefly on a construction site in Vienna, and had more contact with the language. It wasn’t until 1987, between jobs, that I decided to make a real effort to learn German. My main goal was to learn to speak German quickly and naturally. In this post, I’ll share my experience with German and tips for those learning the language.

Why Learn German?

German is one of the world’s major languages, spoken by over 100 million people and central to business, science, and academia. It carries a rich cultural and intellectual tradition—whether you’re drawn to philosophy, history, or classical music, German gives you direct access to that heritage.

While the grammar may seem intimidating, it becomes much more manageable if you focus on listening, reading, and enjoying the process rather than memorizing rules. The key is motivation: stay curious, notice patterns as they appear, and let regular exposure carry you forward.

It’s also important to appreciate German culture for what it is. Sure, Germany doesn’t stir up images of the Mediterranean, endless sunshine, and lively guitar playing. For me, I associate German with reading a good book and listening to Bach on a rainy day. From Charlemagne to Martin Luther, Germany’s imprint on European history shows how a language can be a new window into the human experience.

How I Started to Learn German

I dove into German headfirst. Back then, there was no LingQ, no online resources. So I did what made the most sense—I bought every German book I could find in secondhand bookstores. I remember sifting through an old book from the University of Southern California. It was published in 1959. I also recall Deutsche Kulturgeschichte by Hans-Wilhelm Kelling.

Many of the books that I found were not exciting. They were full of dry texts, vocabulary lists, and grammar drills. I didn’t spend much time completing grammar exercises or memorizing words. My priority was exposure to the language.

I read, and I read a lot. And I listened. I found a cassette tape series with interviews of real German speakers, and listened to them over and over again. I still remember these conversations today. I recall interviews about farmers in Bavaria not finding wives and locomotive engineers. I felt like I was eavesdropping on real conversations.

How I Learn German Today

Through reading and listening, my German became strong enough to read books for pleasure and speak to people with relative ease. I don’t use German as much as I once did, but I can still pick it up again when I need to. If I need to refresh my German, I study German on LingQ—reading, listening to podcasts, and doing a few tutoring sessions.

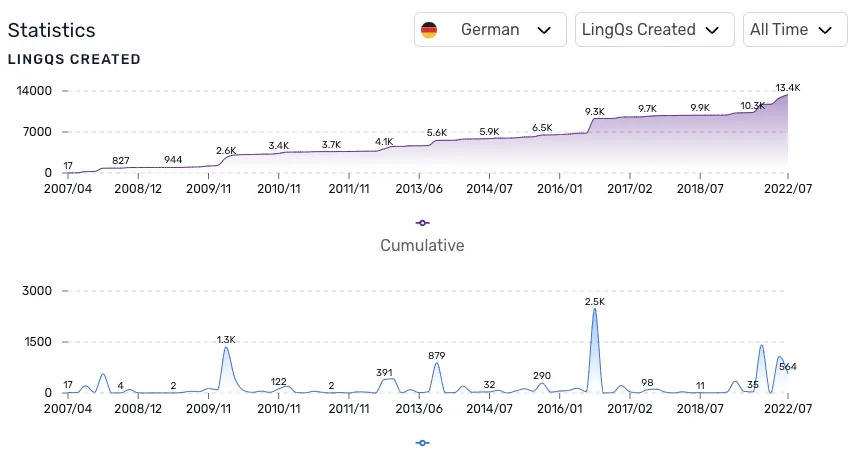

With LingQ, you can access thousands of hours of German content—beginner-friendly mini stories, books, podcasts, interviews, and more. Instead of flipping through dictionaries or struggling with grammar drills, you can listen and read in German more easily. Find interesting German content, look up new words, and automatically save them for later review. Since 2009, I’ve looked up nearly 13,000 words on LingQ.

What’s interesting is that even after not speaking German for a while, I often find that my skills improve when I go back to it. The time I spend learning other languages actually sharpens my ability to notice patterns and refine my skills in German.

Specific Tips for Learning German

Modal Verbs: Patterns You’ll Notice Early

When you immerse yourself in German, certain words pop up again and again. Modal verbs—können (can), müssen (must), wollen (want), dürfen (may)—are among the most frequent. You’ll encounter them constantly.

Modal verbs are useful building blocks for basic communication. After enough exposure, you’ll find yourself saying simple things like Ich kann Deutsch sprechen (“I can speak German”) or Ich will ein Bier trinken (“I want to drink a beer”).

The Challenge of “Der, Die, Das”

German has its quirks. One of the first hurdles learners face is the three forms of “the”: der, die, das. There’s no shortcut—you simply have to get used to them through massive input. I still make mistakes, but I don’t agonize over perfection.

Of course, you can pay attention to these articles and look for patterns. For example, many nouns ending in -ung are feminine, so they take die. However, it’s more worthwhile to develop a sense of intuition through massive input. The more you read and listen, the more you’ll be able to rely on what sounds right.

Talk to Germans Speakers

At some point, you need to engage with other German speakers. Book a private lesson on italki or LingQ, find a language exchange partner, or (if possible) start speaking to some Germans! Speaking puts your knowledge to the test and strengthens your ability to use the language spontaneously.

Find the structures and vocabulary that give you trouble when communicating. Increase your familiarity with natural, spoken German and work on your pronunciation. While speaking does not need to be your priority, it’s a helpful checkpoint and motivation boost in your learning.

Final Thoughts

Learning German has been both challenging and rewarding. It’s opened doors in business, deepened my cultural appreciation, and given me countless hours of enjoyment. If you want to learn German, don’t overcomplicate it. Focus on reading and listening, stay engaged and interested in the language, and keep your motivation high. Fluency comes with time, not tricks.

Interested in more advice on language learning? Check out my thoughts on the best way to learn a language or combine learning with humor by reading this post on German memes.

FAQs

Is German really that hard?

German grammar can be tricky, but with enough input, you’ll notice the patterns. It’s challenging, but not impossible.

Can I learn German without classes or a tutor?

Yes. Massive input—reading and listening—can take you very far. However, tutors are helpful. Speaking German helps guide your learning, maintain your motivation, and activate more of your passive knowledge.

How long does it take to feel comfortable speaking German?

It depends on your effort and motivation, but with consistent input and some speaking practice, you can start to feel comfortable within a year.

How can I start speaking German if I’m focusing on listening and reading?

Start small—I don’t prioritize speaking as a beginner. I recommend speaking with a language partner or tutor once a week at first, and increase the frequency as you become more advanced.

How do I use LingQ to build vocabulary and comprehension in German?

Import content you enjoy, look up unknown words, save them as LingQs, and review them naturally through repeated exposure.

1 comments on “How I Learned German (and How You Can Too)”

Thanks for sharing. You can learn german language by reading blogs, online classes, private tutor, join the institute, etc. The demand for german language is very high in the market. Many MNC wants that type of employee who knows german, so I suggest you must learn german language. Go and join the german language institute in Jaipur.