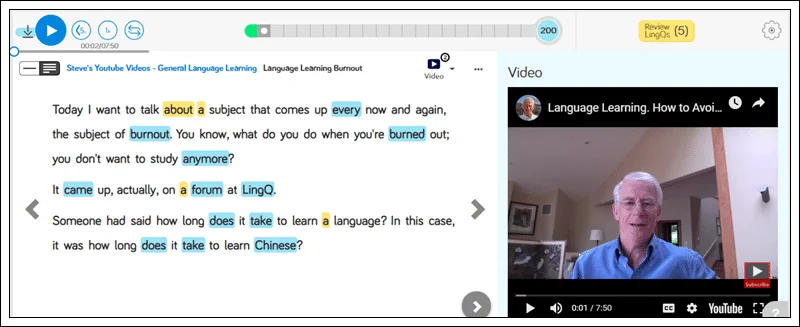

How to Avoid Burnout When it Comes to Language Learning has been transcribed from Steve’s YouTube channel. You can download the audio and study the transcript as a lesson at LingQ.

Hi there, Steve Kaufmann here again. It’s a bit of an overcast, rainy Saturday afternoon here in Vancouver. My wife is practicing the piano, as usual, in the background. Today I want to talk about a subject that comes up every now and again, the subject of burnout. You know, what do you do when you’re burned out; you don’t want to study anymore?

It came up, actually, on a forum at LingQ. Someone had said how long does it take to learn a language? In this case, it was how long does it take to learn Chinese? Someone was talking in terms of years and someone else said well, it depends how many hours you put in a day. Then I said, in my experience when I learned Chinese I was putting in seven-eight hours a day. But someone said well, if you put in too many hours you get burned out.

So I thought about this and I’ve never experienced burnout. When I was studying Chinese I was doing it seven-eight hours, but it was my job. I was paid to learn Chinese. I was employed by the Canadian government. I was a government language student. They paid my salary. I was expected to study the language. Of course I’m going to put in eight hours a day. Languages that I’ve learned since then I’ve been learning, essentially, on my own on my own time, so I’m happy to get in an hour or so a day, but I don’t get burned out.

I guess when I was studying Chinese for the government I had a certain period of time in which I wanted to achieve this British Foreign Service Exam, but in the other languages that I’ve been studying I’m not under any pressure. I do as much as I want. If I had more time, I think I could put in three, four, five hours a day in Czech, for example, because, and I think this is the key, I’m not studying the language so much as I’m gaining this experience and interacting with the language and doing interesting things in the language in the knowledge that, as a result, my skills in the language will improve.

I think if I had to spend my time trying to study and restudy, learn and relearn, memorize grammar rules or tables, answer questions or do any of this study-type work, I wouldn’t be able to put much time into it, I would just stop doing it. So, in that sense, perhaps I would be burned out.

When I look at my Czech now, for example, I happened to go over to Vancouver Island and in Victoria there’s a store, an online store and it’s called CzechBooks.com, I think it is. It’s a wonderful place to buy all kinds of stuff. I’ve bought things via the Internet, but I thought I’m in Victoria; I may as well go and see what’s there because there’s nothing like actually looking at books. So I bought a bunch of CDs, DVDs and books and this book here __________, a short history of Czechoslovakia from 1867 to 1939.

Now, as I’m starting into it there are words I don’t know, but it’s very, very interesting. Here you have the Austro-Hungarian Empire. You have the German-speaking group who, basically, if you want the colonial power much like England was in Ireland sort of thing, had expanded eastward and dominated the Austrian Empire and, eventually, the Austro-Hungarian Empire. So they had the privileges, the German language was given a preeminence and so forth and so on and, gradually, the Czechs through the 19th century start to achieve some recognition of themselves as an independent state.

Then you have the First Word War and now the shoe is on the other foot. The Czechs want to set up their own state, what rights are the German-speaking minority, the ones who have been lording it over the Czechs, denying them their language rights and trying to impose German sort of as part of the whole German-speaking Austria. So you have this whole issue of how that evolves and, of course, these are things I didn’t really focus on. It’s true that the German-speaking minority in Czechoslovakia got the short end of the stick and that might have contributed to events leading up to the Second World War. Then again, they had, basically, tried to suppress the Czechs more or less for quite a long time. So it’s very interesting.

I’m also listening to other things that are of interest. I’m listening to daily news discussions in Czech, so I’m kind of familiar with issues like corruption and so forth that are hot in the Czech Republic. So that’s all interesting and everything I’m reading. I’m following the international news; I’m following the economic crisis in Europe via the Czech media. So it’s interesting.

When I get tired of doing that, I did find a very good book again over there called __________. It’s simpler material where I can get more of the sort of everyday language, which I heard, but I need to listen to it more and more in order to be able to use it. It has the odd grammar explanation which I don’t mind looking at, especially as I’ve become more and more curious about certain things.

So as long as you vary it and do things that are interesting, I don’t see how you can get burned out.

When I was studying Chinese, I mean there’s so much there. History, literature, modern history, ancient history, how do you get burned out? I think the key thing is that you have a goal beyond just learning the language. If your goal is just to learn the language, just to nail down these declension tables or whatever it might be, yeah, I can see where you’d get burned out because after a whole those things won’t penetrate, whereas if you allow yourself to just learn things and learn about things by interacting with the language and reading and listening.

If you have an opportunity, like I also bought some DVD movies, but I can’t understand them yet without the subtitles. I can understand some of the dialogue, but basically can’t understand the dialogue so I’ve put them aside. That’s a bit of a goal now. Maybe two months from now I’ll be able to understand more of the movies. So if you keep it varied like that. As I say, with Chinese there were so many different things I could do with the language I didn’t get burned out, but I guess at the core of it all you have to be interested and so you have to do things that are interesting in order to maintain your interest.

To me, burnout is not a problem. If you want to spend less time at it, you spend less time. I’m not under any obligation to do anything with Czech; I’m doing it out of interest. I guess if someone is at university and they have to pass some exams and they’re sitting there trying to jam or ram certain declension tables or rules into their head, yeah, they can get burned out. I still think those people would be better off if they spent their time doing interesting things with the language and, eventually, these things they’re trying to ram into their brain will fall into place.

So there you have it. Burnout for me is not an issue, as long as you’re doing things that are interesting. When you are less interested or not interested you stop doing them, no burnout.

If you want to access this transcript on LingQ, please go here.