TL;DR Summary

Chinese, Japanese, and Korean each have their unique traits and challenges. Regardless, all three can be learned effectively through consistent reading and listening.

- Chinese has the most logical grammar system and word order for an English speaker, but tones and the writing system are quite challenging.

- Japanese pronunciation is easy, but known for complex grammar. Knowledge of Chinese characters will come in handy, as authentic texts have a high proportion of Kanji.

- Korean has the easiest writing system (Hangul) of the three languages, but its grammar is notoriously unintuitive for an English speaker.

Knowing one language can help with the others, especially if you start with Chinese characters or get lots of input through reading and listening.

Korean, Japanese, and Chinese—what are the similarities and differences between these three languages? How should we approach learning them? To what extent does knowing one help with the others? Based on my experience learning all three, here’s what I’ve discovered.

My Learning Strategies for Korean, Japanese, and Chinese

Mandarin Chinese: Intense and Structured

I spent almost a year studying Mandarin full-time in Hong Kong. It was 1968 and I was a young Canadian diplomat. Canada was preparing to recognize the People’s Republic of China.

My routine was strict and structured. Five days a week, I studied Mandarin for three hours through one-on-one tutoring with a Chinese teacher. Afterwards, I’d spend four or five hours daily reading, listening, and learning characters.

Hong Kong, especially back then, was not an immersive environment for Mandarin Chinese. However, I was able to pass the British Foreign Service Exam for Mandarin within a year. For more details on how I learned Chinese, you can check out this more in-depth post.

Japanese: Independent and Immersed

My experience with Japanese was different. I learned the language entirely on my own while living in Japan. I had the advantage of knowing Chinese characters, which are also used in Japanese. I ended up living in Japan for nine years.

Within a year of studying on my own, mostly through independent listening and reading, I was able to start using Japanese with business contacts. Eventually I became a better speaker of Japanese than Chinese. However, my knowledge of Chinese definitely facilitated my Japanese studies.

Korean: A More Challenging Task

I have been studying Korean in Vancouver intermittently for a few years. I mostly use LingQ to study this language. I am studying independently, as I did with Japanese. However, a major difference is that I am not learning Korean in an immersive environment. Listening and reading are still my main methods for learning Korean, but progress is slower given the less consistent exposure I have to the language.

The Writing Systems

Mandarin Chinese: Consistency is Key

While learning Chinese, I made a special effort to learn the most frequent 1,000 characters. I insist that learning Chinese characters is absolutely essential. I had paper flashcards, and I would practice these characters on the squared exercise books for Chinese schoolchildren.

I developed a primitive spaced repetition system, working with 10-30 new characters per day. My retention rate was not particularly high, but this didn’t matter as I practiced every day until the first thousand characters stuck. This was undoubtedly a good investment of my time.

Whether I remembered the character or had to look it up, I then would write this first character out another five to seven times. Then I placed it a few columns to the right again. At first, I would continue this process for 10 new characters daily. I eventually increased the number of characters I studied daily to 30.

Japanese: Building on Previous Knowledge

My knowledge of Chinese characters proved to be a great advantage when learning to read and write in Japanese. Most beginner texts are written using Hiragana, the main Japanese phonetic alphabet. I persisted in extensive reading, strengthening my familiarity with this writing system. However, as I progressed to more authentic Japanese content, often written with a higher percentage of Kanji, and my background with Chinese became a great asset.

Korean: The Friendliest Writing System

In some ways, Korean is the easiest of the three Asian languages to read. The writing system is called Hangul, an original and unique Korean phonetic script. I found this writing system more approachable becasue 1) at least 50% of the words are clearly identifiable as being of Chinese origin and 2) it’s a much faster, simpler alphabet to learn. You can start reading in Korean more immediately.

Reading Complex Material

I like to read authentic material in order to learn a language. I find newspapers, books, and other material designed for native speakers more interesting than content designed for language learners. To do this, you’ll need a fairly rich vocabulary.

For Chinese, I needed between three and four thousand characters. With Japanese, I started with texts mostly written in Hiragana and gradually challenged myself with texts that contain higher percentages of Kanji. With Korean, the writing system is a much smaller obstacle. However, you still need to read consistently to develop a large vocabulary. Personally, I recommend understanding Hanja when studying Korean, as these Chinese characters are reappearing in Korean education.

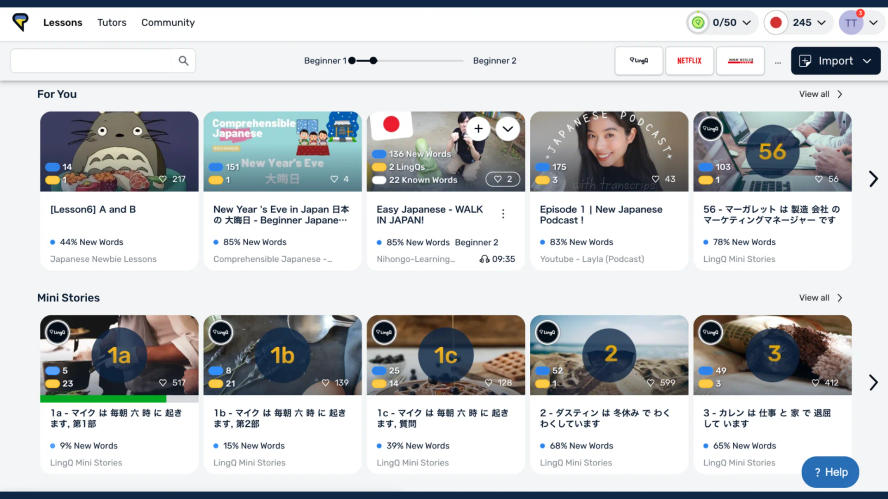

Regardless, whether you’re interested in Chinese, Korean, or Japanese, large amounts of reading and listening is essential. I prefer to study on LingQ because it makes reading in these languages smoother. It’s an optimal platform for a language learner, as you can automatically translate and save new words, test your knowledge with custom review activities, and build up your own personal libraries in each language.

Grammatical Structure

Mandarin Chinese: The Most Similar to English

Language structure and word order in Chinese are easier for English speakers to grasp. The word order is often very similar. Furthermore, the grammar is particularly approachable due to the lack of tenses, case endings, agreements, etc.

Japanese and Korean: A Bit More Challenging

Word order in Japanese and Korean will seem much more different and foreign to an English speaker. In my personal experience, Korean has been the most difficult to grasp. Both Japanese and Korean have different levels of politeness, and this can be an extra challenge for the language learner.

If you want to learn more about grammar and dive deeper into the nuts and bolts of each language, LingQ offers succinct (but thorough) grammar guides for Korean, Chinese, and Japanese.

Pronunciation

Chinese is the most difficult language in terms of pronunciation due to its four tones, which determine the meaning of each word. Unlike English, where intonation is used for emphasis, Chinese relies on tones for comprehension. The actual sounds themselves are not particularly difficult, and many English speakers achieve fluency—like Dashan, a Canadian who became a TV personality in China.

To master tones, I focused on extensive listening rather than memorizing individual tones for each word, which only made me hesitant when speaking. Listening to Xiang Sheng (comic dialogues) helped because comedians exaggerate intonation, making the rhythm of the language more infectious and easier to internalize.

In contrast, Japanese and Korean have no tones, making pronunciation much more straightforward. I didn’t find either language difficult to pronounce. Regardless, pronunciation, like listening comprehension, improves with time and exposure. The more we listen and train ourselves to notice subtle pronunciation patterns, the more naturally we sound like native speakers.

Korean vs Japanese vs Chinese

In summary, all three of these languages are unique with key distinctions to be made. However, my strategy for learning all three has been the same: lots of reading and listening! Before my contact with Asian languages, I perceived them as exotic and very different from what I was used to. However, I grew to find each of these languages fascinating, enriching, and rewarding.

FAQs

Which language is the easiest to learn? Korean, Japanese, or Chinese?

All of these languages are considered difficult for English speakers. However, this ultimately depends on your interests and preferences as a learner. Each language comes with quirks and challenges.

Which language takes the longest to learn?

Due to their complex writing systems, Chinese and Japanese will likely require more time to learn than Korean. For example, Chinese requires memorizing thousands of characters and Japanese uses three writing systems.

Does knowing one of these languages help with the others?

Chinese is a strong advantage when learning Japanese or Korean. Both of these languages have words of Chinese origin. You’ll recognize a lot of vocabulary. Furthermore, Chinese characters come in handy when working with Japanese and Korean writing systems.

What is the hardest aspect of each language?

In short, the biggest obstacle to learning Chinese is the writing system. Korean grammar is not intuitive for an English speaker. Japanese has both a complex writing system and notoriously tricky grammar.

Which language has the easiest grammar?

Chinese grammar is the most intuitive for an English speakers in regards to word order. Additionally, it has no tenses, conjugations, or gender!

10 comments on “Korean vs Japanese vs Chinese”

Comments are closed.

I can testify that it is possible to learn the characters without writing them. I used Heisigs two books of simplified characters (creating ministories or pictures from the individual components/primitives as he calls them) and finished in around 6 months with constant repetition using Memrise, with pronunciation. Now it’s been almost one year since then, and I have been practicing reading using Lingq or just wechat, reaching a fairly comfortable level in terms of speed and vocabulary. I have never devoted much time to writing the characters longhand, except for a period of around one month, when I was attending some classes and had to write notes. The classes however proved to be quite inefficient compared to self-study, so up until now I practice by myself just reading, listening and occassional speaking as I live in China.

I can attest as well that while initially attempting to learn an East Asian language is daunting and sometimes overwhelming and seemingly impossible, it can become nearly natural after years of practice, perseverance, and grit-hard work. I’ve been studying Japanese for over 14 years and I am now living and working in Japan using Japanese in my daily life and feeling very comfortable with it. I’ve never tried learning Chinese, but I have started learning Japanese Sign Language and not only is my knowledge of the spoken Japanese langauge and grammar structure been very helpful for this, my knowlege of kanji has been immensely helpful as sometimes the signs for words in JSL mimick the written kanji for the words. I have also recently started dipping my toes into self-taught Korean and I have found it very refreshing that just by trying to fiddle around with the Hangeul letters, I can start to sound things out in Korean and therefore I can learn the words for things. This is very different from my experience with Japanese where I would sometimes be able to maybe deduce what a kanji character could mean based on its radical componenets and context, and but I would only be making a shot in the dark at how to actually pronounce the word.

I live in Japan 28 years and bad-ass at it,but started learning Ainu again after my first Japanese to Ainu phrase book ,my and the Japanese wife forbade me ,Auynw -ytah yay-paq-as-nw-ye-qar war wa yn-qar Shy-sha-mo ytah twp-qy-qar =an ne -e pyrqa-re no e-a-o-ro-o-ytah wa nw-qar -a-s-qa-y ne-e.Hopefully Ainu will become like English Paq-qo-ytah obligatory language.see online version ( Apple app store ‘Puffin’ browser will allow you to read on iPhone ainutopic.ninjal.ac.jp,you can learn 3 languages En,Jap,Ainu.

i am korean but i always find myself trying to speak in japanese to my mother for some reason.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve really enjoyed browsing your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!

One thing I want to add is, writing Chinese characters is tricky even to native Chinese speaker. I moved to US for over 20 years and as soon as social media becomes a thing, the need for me to write by hand quickly went down. Because of that, I found myself forgetting the writings of many Chinese characters.