Today I want to write about Japanese verbs and Japanese verb endings, but first I want to make a confession.

I write these blog posts based on topics that cross my mind for whatever reason. I write them without an awful lot of planning because I find that, when it comes to language learning and talking about languages, spontaneity is somehow more effective than too much systemization. So I have no terms to describe Japanese verbs.

The reason I am on this subject of Japanese verbs is that in a video that I made quite a while ago about Japanese I said there are no verb endings to worry about in Japanese and someone commented saying there are. And, of course, when I think about it that person is right. What I had meant to say was that I have never consulted Japanese verb tables the way I have consulted verb tables for Spanish, Portuguese, even declension tables fo Russian and so forth because there are not as many different possible endings as in these other languages. Or rather, endings don’t change as much for tense and person.

So how do Japanese verbs work and why is it that I never really looked upon them as having the same verb ending problems as these other languages? Mostly, I just got used to Japanese because, in Japanese, not only for verbs, but for adjectives, adverbs and nouns there are endings that determine the function of that word in a sentence and with enough input, listening and reading, and eventually using these, we just get used to these patterns. I don’t find I have to consult tables to refresh my memory on the different endings, the way I do in Romance languages for example.

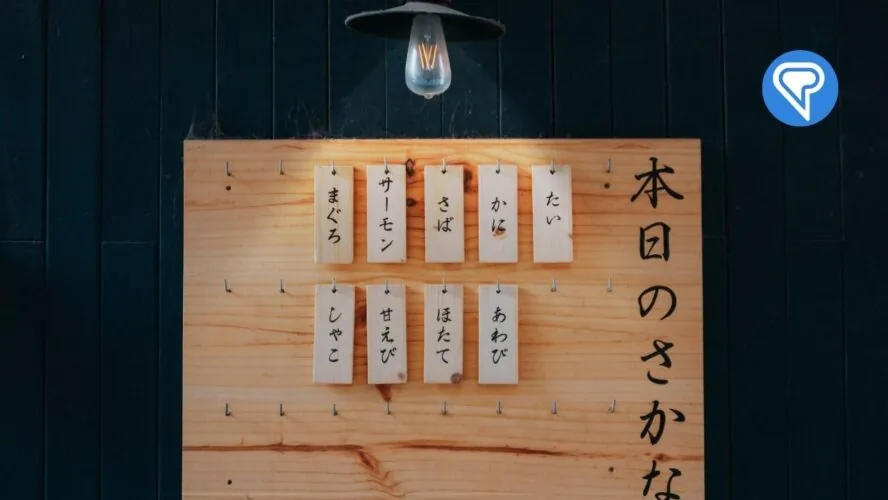

Let’s look at some examples…

“Kaku” is to write. “Kakimasu” is more formal. If it’s past tense it’s “kakimashita”. But, again, it doesn’t change for “you”, “I”, “we”, “they”, and so on. To imply a level of uncertainty, and this includes a sense of the future, we say “kakudaroo”, to mean “I may write”, or “am likely to write”, or even “I will write”. We can also say “kaku deshoo” to mean more or less the same thing. If these explanations are vague, it is because a true sense of how these are used only comes from lots of input and, eventually, output. You start to get a feel that no explanations nor verb conjugation tables can give you.

To suggest a conditional sense, as in the English word“if”, the ending can be “tara” as in “kakimashitara” or “kaitara” using the past tense of “kaku” (“kakimashita” or “kaita”). Or you can use the present tense with “kaku” and add “nara” or “naraba”, or go “kakeba”. So there is a variety of ways of saying ‘if” and you just have to get used to them all, to that you understand them all, and eventually start using some of them.If you are asking or getting some else to to write something it’s “kakasareru”.

But I am just teasing you. There is a long list of these, far too many to learn and remember. I don’t intend to provide an exhaustive list of these endings and how they change the meaning of the verb “kaku” (to write). There are a lot of them. As you come across them, look them up, or skim some explanations, and just keep on meeting them in your listening and reading, they just start to gain meaning.

If I were to just look at a table of these, I don’t think I could learn them or remember them, or even get any sense of how they are used. But if I see these forms of words in different contexts I start to get used to them. Only then would it be useful to consult such tables to confirm what I have experienced.

Japanese works differently from European languages that we may be more used to. Adjectives work the same way as verbs in how their meanings are affected by endings.

Take the word “yasui”, which means inexpensive, cheap. “Yasui daroo”, like “kaku daroo”, (probably write), means “probably inexpensive” or even “don’t you agree that it is inexpensive?”. Nouns and adverbs can work this way with the ending conveying a sense of uncertainty, or likelihood, and implying “don’t you think that?”. To get a feel for these requires a lot of input and a willingness to continue to absorb the language, in all its newness and uncertainty, until our brains start to get used to these new patterns. Of course you can read grammar explanations, but things won’t really click in until you have had enough exposure.

So, basically, I don’t see this as a question of verb conjugations per se. I just see these things as suffixes, call them endings, that have meanings that are attached to verbs, nouns, etc., and there’s a large number of them.

There is a lot of redundancy in Japanese. Playing with this redundancy for effect is one of the pleasures of the language to me. Just to think of one example. “Naze” means “why”. You can say “naze daroo” which literally could be translated as “why is it likely?” but it really just means “why”.

And then there is “nazenara” or “nazenaraba”, both of which mean “because” but could be translated as “if why”.

Every language has its idiosyncrasies which are the delightful unique features of that language. In the case of Japanese, it’s playing with all these different things that get stacked onto the end of words to shape what we’re trying to say, and enable us to inject a certain amount of typical Japanese hesitation, vagueness, understatement, indirectness or even just more time think about what you’re going to say. These are all part of the art of communication, Japanese style, which I love. It’s not about conjugation tables!

So this post is in response to the person who corrected me when I said there are no verb endings in Japanese. In fact there are different endings in Japanese, endings that affect the meaning of words, but this is not like verb conjugations in European languages.

Is Japanese hard to learn? Check out this LingQ blog post to find out what we think!

Enjoyed this post? Check out this LingQ blog post to learn some fun Japanese tongue twisters!

comments on “Learning Japanese Verb Endings”

Comments are closed.