When deciding how to go about learning a language, it’s logical to turn to the U.S. Foreign Service Institute (FSI). Given the institution’s ample experience in language instruction, one can’t help but wonder how diplomats learn languages.

In this post, I’ll summarize and share my thoughts on the following:

- How the FSI ranks languages by difficulty

- The learning methods used by the FSI

- FSI estimates regarding the amount of time needed to reach fluency

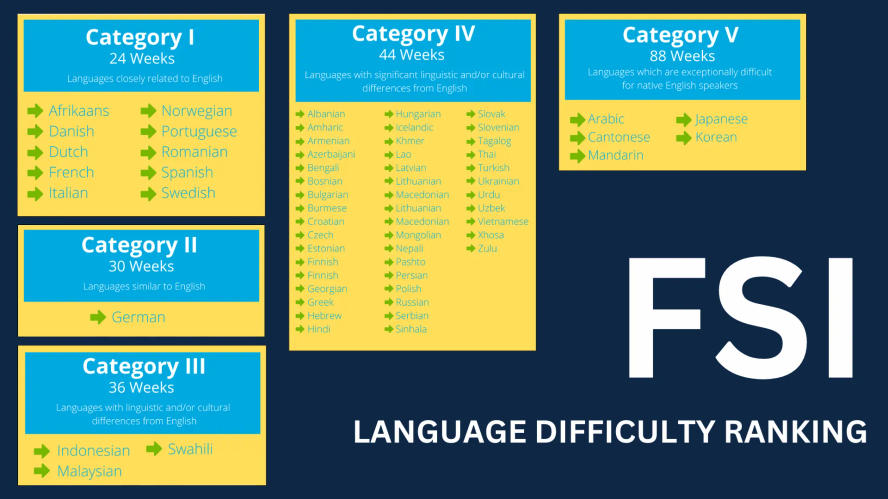

The FSI Language Categories

The FSI categorizes languages into five levels of difficulty for English speakers, from Category 1 (easiest) to Category 5 (most difficult). The criteria are clear: the more distant a language is from English in terms of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation, the longer it takes to learn. For example, Dutch or Spanish are Category 1 languages while more “distant” languages, such as Russian or Hindi, are Category 4 languages.

My Thoughts on FSI’s Language Difficulty Rankings

Most of the rankings are logical. Languages with similar scripts, more vocabulary words in common, and consistent pronunciation all help us learn more quickly. However, from personal experience, I wouldn’t expect Danish to be considered a Category 1 language. Its pronunciation is more difficult to grasp.

Also, I find that the emphasis on the language’s writing system could be higher. For example, Persian and Czech sharing the same category seems bizarre to me. Persian’s writing system is a major obstacle for many language learners.

Overall, I find the FSI chart useful as a rough guide. However, personal experience and motivation often defy these neat categories. If you really want to learn Japanese, you might find the experience of studying Japanese much more pleasant than forcing yourself to power through Italian. Ultimately, your preferences and reasons for studying the language are more important than its similarity to English.

A Quick Breakdown of FSI Learning Methods

Here is how diplomats learn languages in the United States. The FSI teaches through intensive classroom instruction. It’s typical to undergo five hours of instruction daily for about 30 weeks. Students learn in groups of three with one instructor. Materials, in the form of audio and reading, emphasize drills and scripts.

Having gone through intensive Chinese courses myself, I think 5 hours of instruction is a bit much. There’s a balance to be had between instructional time and independent study. While learning Chinese, I had 3 hours of daily instruction, but I supplemented my studies with lots of independent reading and listening.

How I Would Approach Intensive Learning

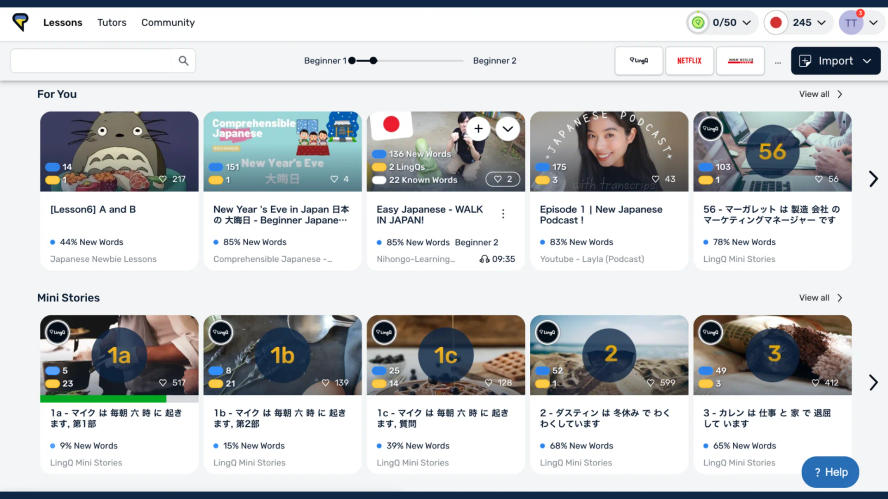

Where FSI focuses on accuracy, performance, and repetition, I would advocate for more emphasis on input-rich exposure: listening, reading, and engaging with real-life content. Today, we have an abundance of online resources — podcasts, YouTube videos, articles, movies — far beyond what the FSI originally designed their curriculum for.

FSI prescribes structured content, but I think how diplomats learn languages overlooks the joy and richness of personalized reading and listening. A curriculum forces our path, whereas I prefer to acquire language through following my own curiosities. For example, I like to to Lebanese news in the kitchen, import it into LingQ, and study the material more thoroughly.

Given that you genuinely enjoy the content you interact with, engagement with the language outside of the classroom will be higher and more consistent.

How Long Does It Take to Learn a Language?

The FSI claims that learners can reach an S3/R3 level (roughly B2-C1) in 24–88 weeks, depending on the language. I’m skeptical about this. B2, for example, is a high level. Speaking fluidly and understanding natural speech without simplification takes time. Sure, you can cram for months and perform well in rehearsed, structured settings, but true fluency is not something that can be rushed.

Languages need time to gestate. After intensive study, I’ve found that my language continues to improve merely through continued exposure. The takeaway is that language learning isn’t linear. It’s a long-term process, deeply tied to how much time you spend immersed in the language — not just learning it, but living it.

Final Thoughts: Stay With the Language, Enjoy the Journey

How do diplomats learn languages? In short, diplomats learn with definitive deadlines through intensive instruction that emphasize scripted situations. Fortunately, most of us don’t have to learn this way. We learn languages with the luxury of enjoying the process.

Instead of stressing about how long it takes to learn a language or whether or not you’ll achieve a certain level, just enjoy the language. If you love Arabic music, you’ll keep listening. If Japanese culture fascinates you, you’ll keep reading. If you enjoy something, you stay with it — and that is what leads to long-term fluency.

So when someone asks, “How long will it take me to learn a language?”, maybe the better question is:

“Can I find something I love in this language that will keep me coming back?”

Because if the answer is yes, time becomes less important — and fluency becomes inevitable.

comments on “How Diplomats Learn Languages”